October and November were busy months for the Historical Medical Library! We launched our blog, announced that our collection of anthropodermic (human skin) books is the largest in the United States, held several impromptu pop-up exhibits, and hosted an Archives Month Philly event.

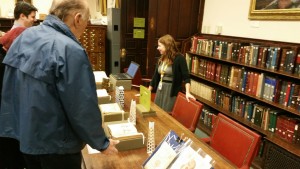

Our pop-up exhibits have been received with enthusiasm and we love surprising Museum visitors with the opportunity to visit the Library and see our collections. The exhibits in October were focused on the concept of “monster” as used as a medical term over the past 500 years, and culminated in our Archives Month Philly event, “The Monstrous, Fabled & Factual: Exploring the Meaning of ‘Monster,’ 1500-1900.” (You can read our previous post about Archives Month here.) The exhibits in November displayed our “Favorite Things.”

This year was our first time participating in Archives Month Philly. It was fantastic to invite everyone, show off our collections, and talk about them with our peers. We feel like our Library has been “hidden” for so long – especially to the general public – and Archives Month was the perfect opportunity to show people that we exist and have interesting collections!

Another exciting aspect of our Archives Month event was reaching out to an undergraduate English class, “Monster in Film and Literature,” at the University of Pennsylvania. We invited them in for a special viewing of “The Monstrous, Fabled & Factual” to supplement their curriculum. Exposing special collections to students is so important – it teaches them the value of primary sources, aids in learning how to compare texts, and provides physical access to rare materials rather than digital surrogates.

We asked the students to select one of the texts on display and describe how the image may have helped the reader understand the concept of the “monstrous.” This allowed the students to interact with the materials rather than be just passive viewers. All of the responses were thoughtful and well-written. Here are a few that highlight some of our favorite texts:

“The pictures that represent Biephalus and Derodidymus help the reader better understand the connection between science and monstrosity because of the anatomical depiction of the twins. With Meckel’s text that introduced pleiotropy, more people began to shift their views of monstrosity to an effect of natural science. Stripping the ‘monster’ of conjoined twins down to its skeleton reveals the human like qualities that are not as visible to outsiders.”

“The image of the human-chicken really illustrates how the understanding of ‘monstrosity’ began to change. The labels [in the image] are much more helpful in pointing out specific deformities rather than simply a drawing of a monster/hybrid exaggeration.”

“In the illustration of the extremely hairy woman, it is the disruption of the familiar human form with something unfamiliar that creates an image of monstrosity. The excessive amount of body hair, a non-human physical characteristic, makes the reader understand the addition of animal physiology to the human body to be abnormal, or thus, monstrous. The woman looks mostly human, but there is something off that makes the reader question what she is and how she came to be that way.”

One of the most important jobs of archivists and librarians is to provide access to their collections and encourage people to consider them, not only as objects, but as chapters in the narrative between the past and the present. (Archivists and librarians dearly love to show off their “stuff.”) Here at the Historical Medical Library, we are always looking for opportunities to do just that. Keep an eye on our Twitter account @CPPHistMedLib for the date of our next pop-up exhibit!