-by Beth Lander

On Wednesday, July 15, 1868, a 28 year old woman named Mary Lynch was admitted to Old Blockley, Philadelphia’s almshouse, officially known as Philadelphia General Hospital (PGH). Old Blockley was located at what is now the intersection of 34th Street and Civic Center Boulevard, on the southeast corner of the University of Pennsylvania. Blockley was where you went when you could not afford care in a private hospital.

The Women’s Receiving Register from PGH lists a small amount of information for each patient: name, birthplace (a country, if other than the United States. Mary was born in Ireland.), age, temperate or intemperate habits (Were you a drunk, or not?), date of admission, ward, color and diagnosis.

Mary suffered from phthitis, an archaic term for tuberculosis of the lungs. She was listed as being of temperate habits.

The summer of 1868 was hot – temperatures during the week of Mary’s admission hovered in the high 80’s. Friends or family members were thoughtful, and brought Mary pork and bologna to supplement her hospital diet.

Unfortunately, the pork products they brought were tainted with Trichinella spiralis, a parasitic roundworm frequently found in pigs. Trichinella is passed directly from one host to another by ingestion of muscle tissue that has been infected with the encysted larval stage of the parasite. Once in the small intestine, the larvae develop into the adult stage. After mating and reproduction, newborn larvae leave the intestine and migrate through the circulatory system to muscles throughout the body. The total time for this cycle to occur is 17 to 21 days.

Mary was admitted to Ward 27, where her attending physician was Dr. William Botsford. Botsford was just 24 years old. He had received his medical degree at the age of 23 from Jefferson Medical College.

Attending to other patients on Ward 27 was Dr. John Stockton Hough. Hough received his M.D. from the Medical Department of the University of Pennsylvania in 1868. He, too, was 23 years old. Hough was resident physician at Old Blockley during the year 1868-1869. One of his research interests was encysted trichinosis.

Mary spent a little over six months in Old Blockley. She died on Saturday, January 16, 1869. Due to the wasting nature of both the tuberculosis and the trichinosis, Mary, who was 5’ 2” tall, weighed 60 pounds when she died. She was buried later in January in a pauper’s grave on the Almshouse property. No specific dates of burial were provided for patients who died at Old Blockley.

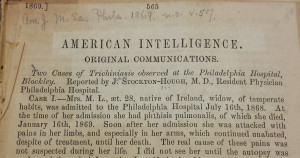

At some point between her death and her burial, Mary was autopsied by Dr. Hough. His graphic depiction of the encysted trichinosis that lead to her death was published in 1869 in the American Journal of Medical Sciences. To say that the number of parasites that made host of her body was grotesque would be an understatement.

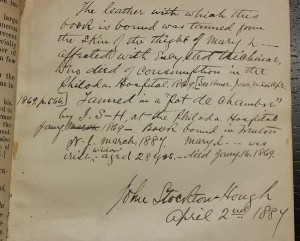

Either before or after the autopsy, Dr. Hough removed a piece of skin from Mary’s thigh. He took the skin to a basement room in the Almshouse and tanned it in a chamber pot.

Traditional 19th century tanning began by soaking an animal skin in lime water. After the skins had soaked, any flesh, fat and hair was removed from the skin by hand. The “defleshed” skins were again soaked in lime water for a few days, and then soaked in baths of tannin, usually derived from tree bark, that were made progressively stronger over a period of weeks or months. Once “tanned,” the skins were dried, rolled and pressed into leather.

Would Dr. Hough have used such a traditional method of tanning in a chamber pot in the basement of the hospital in which he worked? Perhaps he used urine, a substance that would have been in abundance in the hospital, in order to prepare the skin. Urine was used for thousands of years as a quick way to dissolve fat, flesh, and hair from a skin. Do-it-yourself enthusiasts today tan fish skins in a one-to-one mixture of urine and water that has stood for up to two weeks in order to intensify the ammonia that is naturally present in human waste.

Any tanning method used would have taken at least two weeks to a month if not months to fully cure Mary’s skin.

Dr. Hough was listed as a physician living at 2003 Walnut Street in Philadelphia from 1871 to 1877. He married Sarah Wetherill in 1874, and left with her for an extended trip to Europe. There, Mrs. Hough became pregnant, and gave birth to a daughter in December of that year. Sarah died in Italy on January 10, 1875.

While there is no evidence that Hough practiced medicine after 1877, he did write articles on topics such as hygiene, biology, speculative physiology and statistics, and he developed a number of surgical instruments.

Hough was also a bibliophile, and began amassing a collection of medical texts that supported the publication of his catalog Incunabula Medica in 1889. When he died in 1900, the estate inventory lists his library as being assessed at $900.00, the second most valuable piece of property in his estate.

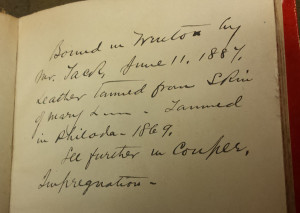

He married his second wife, Edith Reilly, on June 30, 1887. At that time, Hough lived at 827 Madison Avenue, New York, New York. Hough later settled near Trenton, New Jersey, and had five children with his second wife.

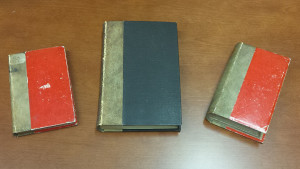

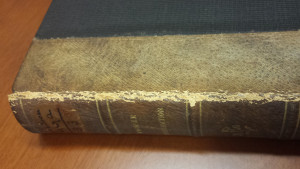

It is in Trenton where the extant part of Mary reaches its final resting place. In June of 1887, weeks before he remarries, Hough takes Mary’s skin and uses it to partially bind three books: Speculations on the Mode and Appearances of Impregnation in the Human Female…published in 1789; Le Nouvelles Decouvertes sur Toutes les Parties Principales de L’Homme et de la Femme… published in 1680; and Recueil des Secrets de Louyse Bourgeois…published in 1650. Each of these books deals with female health, conception and reproduction.

In each, he inscribes a brief note about Mary, protecting her identity by calling her “Mary L___.” One book, though, contains more than enough information about Mary, her admission and death dates, and her cause of death to be able to locate her in the PGH records at the Philadelphia City Archives.

These three books, in addition to the other two anthropodermic books in the Library collection, represent a unique convergence of text and medical specimen. The books as collections of text remain valuable sources in the history of medicine. The books as objects force us into uncomfortable considerations of the use of human skin in bindings: Was Mary memorialized in these books? If so, why did Dr. Hough keep her skin for nearly 20 years before using it?

Why did Dr. Hough use Mary’s thigh skin to bind books about conception and childbirth? What, if anything, was he saying about Mary, or women in general? Were other people aware of what he was doing?

Does the use of human skin diminish the value of the books as text, and render them nothing more than objects of morbid curiosity?

I worked as a page in the historical section in the early 1970s and I could have sworn that there were more anthropodermic books. I don’t remember their names, but one was in The Cage although I don’t think it was that old, and when you opened the book you saw a note that this book was made with the skin of a confederate soldier. Also, I vaguely remember several in a special collection – maybe the Solis-Cohen collection? – that had tipped into the books a note with the name and reason for death of each person whose skin was used for that book. The notes were quite elaborate on the hospitalization of each “skin donor”.

Hi Lynn,

You are right – the three “Mary” books aren’t the only anthropodermics we have. We have, in total, five. We chose to highlight these three because it’s an interesting story! Earlier in the year, we had sent out the books for testing (See our previous blog post for the details!). One of the other two also belonged to Dr. Hough. The book with the skin of Confederate soldier was donated by S. Weir Mitchell, and although it’s definitely bound in human skin, there’s no way to be sure the binding was “donated” by the soldier.

I checked briefly in the Solis-Cohen collection and did not find any other books, but will keep looking! This is very exciting for the Library.

This is so fascinating! I cannot wait to visit the museum!!!!!!

Keep an eye on our social media channels – the Library is doing impromptu pop-up exhibits this month, which means that you’ll get to see some of our cool stuff during your visit to the Museum! We’ll post the day before one is happening.

I find this so fascinating. On my first visit to the museum I saw the display with the books bound with human skin. I was shocked to see the name “John S Hough” listed as the binder because that happens to also be my grand fathers name. A little research later, I discovered this John S Hough is my great great grand father. I love having the opportunity to find out about the lives of my ancestors thanks to the museum!

Hi Nicole,

It’s great that you were able to see the books when they were on display in the museum. How exciting that John Stockton Hough, the donor of 3 of our our anthropodermics, is your great-great grandfather! Dr. Hough also donated a good many rare books to the Historical Medical Library as well.