– by Paul Braff*

In 1896, statistician Frederick Hoffman confirmed what Charles Darwin and other scientists and doctors had asserted for years: African Americans were going extinct.[1] Within the context of the burgeoning professionalization of the medical field, such a conclusion had the potential to omit African Americans from medical care, especially when combined with the preconceived racial differences of the time. Indeed, white physicians in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries frequently wrote African Americans off as a lost cause, categorized the race as inherently unhealthy, and refused to treat black patients or used heavy-handed tactics, such as forced vaccinations, to improve black health.

To fight this perception, in 1915 Booker T. Washington inaugurated National Negro Health Week (NNHW), a 35 year public health campaign, and the subject of my dissertation. Washington, and his successor, Robert Moton, ran the Week for its first 15 years out of Tuskegee Institute. After a brief transfer of control to Howard University, the U.S. Public Health Service (USPHS) decided to take over the Week in 1932. Under the leadership of Roscoe C. Brown, head of the Office of Negro Health Work, the campaign blossomed. Participation estimates increased from 475,000 in 1933 to millions by the mid-1940s as the Week became a National Negro Health Movement and increased its focus on year-round health improvement.

The size, scope, and mission of the Week, which specifically targeted health messages to those ignored by the medical establishment, drew me to choose the Week as my dissertation topic. I began my research at Tuskegee University, which has the archives of the Week through 1930. However, aside from this collection, the archives are surprisingly sparse. While there are many newspaper and journal articles about the Week after 1930, the actual records and discussions of the Week’s leadership have been lost. Combing Howard University and the National Archives, both archivists and historians have come up empty in finding either the records of the Office of Negro Health Work or the personal papers of Roscoe C. Brown.[2]

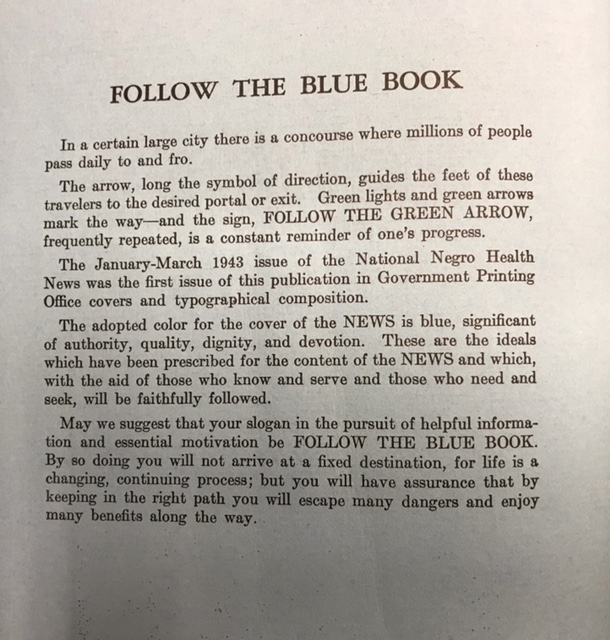

Such a loss means that every document and collection related to the Week is vital to those wishing to better understand how the USPHS expanded the Week and how those in the medical establishment perceived their African American audience. It is here that the Historical Medical Library of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia fills an important gap. Its vast resources include original versions of the Week’s quarterly publication, the National Negro Health News. While copies are available, the originals include color bindings, which Brown chose to convey specific messages. For example, the blue binding the News used until 1947 signified, “authority, quality, dignity, and devotion.”[3]

Although a copy of the News would have provided me with the same information about the significance of the blue color, the passage above is the only reference to the cover color in the 18 year history of the journal (1933-1950). Without the original journals, there would be no way to know how long the blue cover remained or to know that the cover changed color several times, such as to brown and then red in 1947. These color changes signal alterations in emphasis, message, or even funding that an examination of copies would miss and opens new avenues into understanding the Week that scholars might easily overlook. Additionally, these color covers provide a clearer aesthetic as to what Brown and the Week’s leaders intended for the journal.

Another area that the archives help illuminate is the amount of autonomy within the Week. When Washington originally created the Week, he used a grassroots approach. Communities were free to celebrate the Week at different times of the year and in a variety of ways. While he and Moton published a pamphlet that included themes to each day of the Week and suggestions about how locals could organize an NNHW, communities largely chose their own goals and methods of celebrating based on local needs and resources. As might be expected, the USPHS takeover in the early 1930s led to a more standardized approach to the Week’s activities. Under the USPHS, the members of the medical establishment, doctors, nurses and public health officials, were the keys to the Week and with the vast resources of the USPHS behind them they came out in droves to support NNHW. The number of lectures, films, radio programs, and exhibits providing health information and instruction increased substantially during the early stages of USPHS leadership of the Week. Conversely, during the same period, grassroots activities led by non-medical establishment personnel, such as planting projects or cleaning areas other than homes and lots, decreased dramatically.

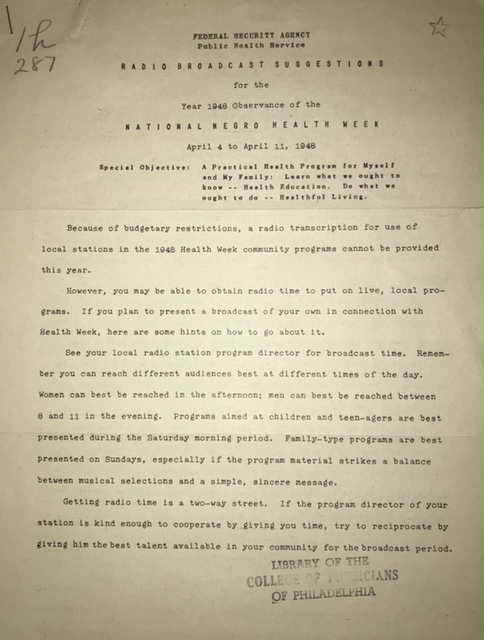

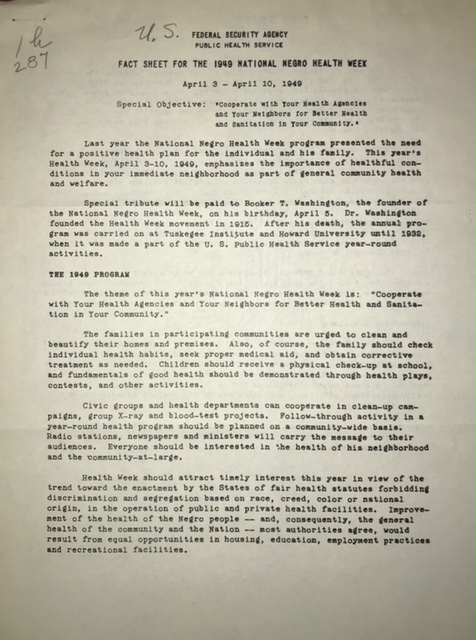

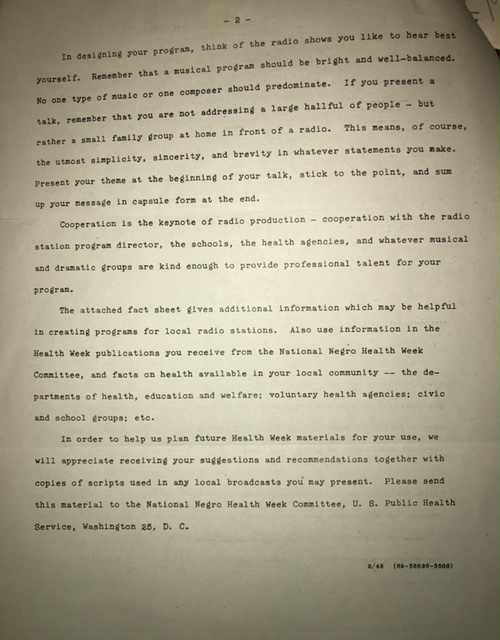

However, examining the NNHW materials at the College of Physicians of Philadelphia indicates that even by the late 1940s, local grassroots organizers still had significant independence within the Week. According to Brown, an important element in transmitting health messages over the radio in the late 1940s involved entertainment. Specifically, Brown emphasized that broadcast speakers use “the utmost simplicity, sincerity, and brevity” when giving radio talks.[4] He also encouraged the use of music during the broadcast. Here, music served two purposes. First, it could generate greater cooperation in the Week within the community by providing local musicians with an opportunity to demonstrate their talents. Second, it could attract a larger audience that tuned in for the music and stayed tuned in for the talks after. Yet it was up to the local organizers to pick the music most suited to their audience and to identify what brevity meant for their own communities. Brown did not provide examples or specifics, allowing great leeway in the creation of these local broadcasts on health.

Brown’s advice on creating radio broadcasts also noted that different types of audiences listened to the radio at different times: families on Sundays; children and teenagers during Saturday mornings; etc.[5] This observation indicates that local leaders had wide latitude in the ways in which they could get the Week’s health message out to the public and what kinds of people to target with health messages. Some focused on children, promoting a particular health concept, such as cleaning the home, and then centering the Week’s activities around the children’s efforts. Other leaders concentrated on attacking specific diseases, such as syphilis or tuberculosis. Here, leaders targeted adults, instructing them on the ways in which to combat these diseases and the importance of seeing a physician regularly.

This material, unexamined by previous NNHW researchers, illustrates the continued importance of non-medical grassroots elements within the Week, even as doctors came to dominate the Week’s organization locally and nationally. These documents also provide insight into the thinking of Brown and the USPHS as enthusiasm for the Week began to falter in the late 1940s. Indeed, Brown’s instructions raise questions about the ability of physician organized radio broadcasts to relate to the general African American public and the degree to which that public internalized the health messages it heard. Thus, the materials at the College of Physicians of Philadelphia provide further understanding into how and why the Week came to a sudden end in 1950 outside of the rote explanation that African American physicians grew more antagonistic towards a campaign that singled out their race.[6]

Sources

[1] Charles Darwin, The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex (London, UK: John Murray, 1871). Reprint. New York, NY: Penguin Books, 2004, 163; Frederick L. Hoffman, Race Traits and Tendencies of the American Negro (New York, NY: The Macmillan Company, 1896), 35; George Frederickson, The Black Image in the White Mind: The Debate on Afro-American Character and Destiny, 1817-1914 (New York, NY: Harper and Row, 1971), 236-237, 252-258.

[2] In consultation with Tab Lewis, NARA Archivist, and Sonja N. Woods, Archivist at the Mooreland-Spingarn Research Center at Howard University, I was unable to locate the records of the Office of Negro Health Work or the personal papers of Dr. Roscoe C. Brown. I come to the same conclusion that Susan L. Smith did more than twenty years ago when she determined that neither of these records are available anymore. See Susan L. Smith, Sick and Tired of Being Sick and Tired: Black Women’s Health Activism in America, 1890-1950 (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania, 1995), note #4 on 191.

[3] National Negro Health News, Vol. 11, No. 1, January-March, 1943, back cover.

[4] “Radio Broadcast Suggestions for the Year 1948 Observance of the National Negro Health Week,” US Public Health Service, Federal Security Agency, 2, 1h 287; “Radio Broadcast Suggestions for the Year 1949 Observance of the National Negro Health Week,” US Public Health Service, Federal Security Agency, 2, 1h 287.

[5] “Radio Broadcast Suggestions for the Year 1948 Observance of the National Negro Health Week,” US Public Health Service, Federal Security Agency, 1, 1h 287; “Radio Broadcast Suggestions for the Year 1949 Observance of the National Negro Health Week,” US Public Health Service, Federal Security Agency, 1, 1h 287.

[6] David McBride, From TB to AIDS: Epidemics among Urban Blacks since 1900 (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1991), 125-145; Susan L. Smith, Sick and Tired of Being Sick and Tired: Black Women’s Health Activism in America, 1890-1950 (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania, 1995), 76-81; Edward H. Beardsley, A History of Neglect: Health Care for Blacks and Mill Workers in the Twentieth-Century South (Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press, 1987), 245-272.

*Paul Braff is a Ph.D. Candidate in the Department of History at Temple University. He is a 2017-2018 Fellow of the Consortium for History of Science, Technology, and Medicine.