“If [medieval] culture is regarded as a response to the environment then the elements in that environment to which it responded most vigorously were manuscripts.”

– C. S. Lewis, The Discarded Image: An Introduction to Medieval and Renaissance Literature

The Historical Medical Library, as part of the Philadelphia Area Consortium of Special Collections Libraries (PACSCL), is participating in a CLIR grant to digitize Western medieval and early modern manuscripts held by libraries in the greater Philadelphia area. The Library is lending thirteen medical manuscripts dating from c. 1220 to 1600 to this project, called Bibliotheca Philadelphiensis (BiblioPhilly). Our manuscripts will be digitized at the University of Pennsylvania’s Schoenberg Center for Electronic Text and Images (SCETI) and the digital images hosted through the University of Pennyslvania’s OPenn manuscript portal and dark-archived at Lehigh University.

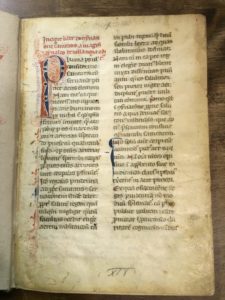

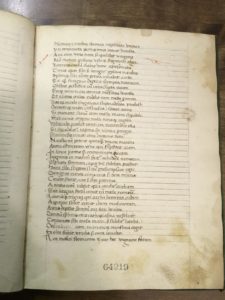

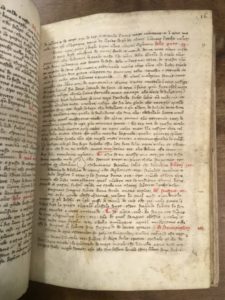

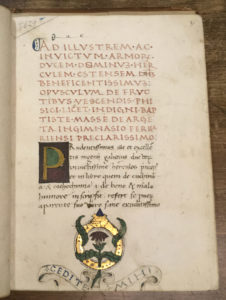

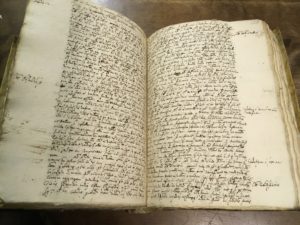

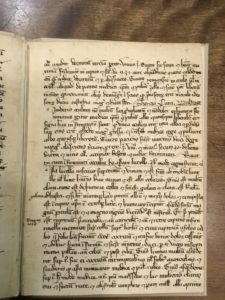

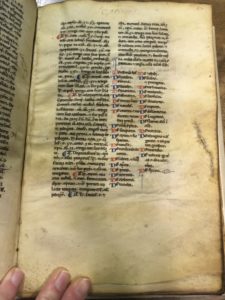

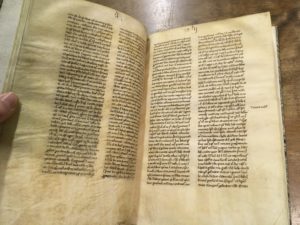

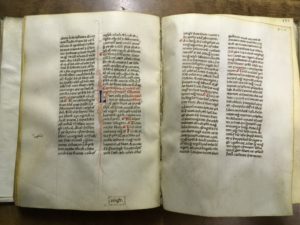

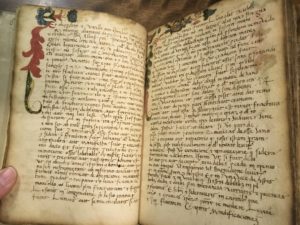

Why digitize books that are over 400 years old? What value can they bring to our lives? Some medieval manuscripts contain the only copy of a text copied contemporaneously to when it was written. The scripts show readers the evolution of handwriting (the study of handwriting is paleography), just as the dialect or language used helps determine the geographic origin and date of the manuscript. Grotesques and other marginalia reveal the symbolism attributed to animals and what contemporary society thought was important to emphasize (or ignore). Glosses written in by later readers and ownership marks tell the story of manuscript’s use, as do rubbed or crossed out images and text. For those interested in codicology (the study of books as physical objects), medieval manuscripts illustrate early bookbinding techniques, how paper and parchment were made, and the composition of inks. In short, medieval manuscripts can tell us much about what their societies thought, believed, found important or wanted to dismiss or omit; how items like leather, parchment, paper, and ink were created; and the dissemination of knowledge.

One of the most obvious reasons for digitization is an archivist and librarian’s favorite word: access. Digital surrogates provide researchers with the ability to study from anywhere in the world at any time on any day. Scholars who may not have funding for travel or who need immediate access, teachers in classrooms all over the world, or someone newly interested in medieval manuscripts can instantly view, study, and learn from a library’s digital holdings.

Digitization not only increases the opportunity for access, but also plays a large role in the preservation of the book. While we as librarians and archivists want our collections to be available to all researchers, we must also take care of the physical object. Older books can be fragile and are best physically handled as little as possible. Loose bindings, brittle paper, flaking or fading ink, warping due to humidity, and red rot can be exacerbated by touching and exposure to light or heat. Digital surrogates provide a way to examine the text closely without causing further damage to the book; they are a way to ensure we can balance two important parts of our jobs: preservation and access.

Another reason to digitize? If access and preservation are not persuasive enough, outreach may do the job. Having digital images from medieval manuscripts means that new audiences can be easily introduced to them. Images of what makes a manuscript remarkable, or what makes it ‘typical’, can reach potentially thousands of people through social media. With Peter Jackson’s film interpretations (2001-2003) of J. R. R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings series, the “medieval” world became more accessible to the general public. The explosion of the fantasy genre has made a medieval-like world ubiquitous in modern pop culture, and by sharing tangible pieces of the past in approachable ways, historians and special collections professionals can also share the importance of history to modern everyday life.

Digitization also provides scholars with the ability to annotate directly on (!) a folio and to collaborate easily on transcriptions, textual or script comparisons, or other projects with colleagues across the world. The Mirador image viewer allows one to place digital images from different repositories or manuscripts side-by-side for comparison and to annotate directly on the image, line-by-line or by selecting a specific area of the folio.

In 2016, we may take for granted the ubiquity of digital content available from libraries and the tools with which to manipulate it. However, digital libraries have been curated for only twenty years or so. The British Library was one of the first to provide digital surrogates. In 1994, the British Library launched its Initiatives for Access program, meant to make its collections more accessible to the public using new technologies. During its first foray into digital surrogates, the British Library published the Electronic Beowulf in conjunction with Anglo-Saxon scholar and University of Kentucky Professor of English, Dr. Kevin Kiernan. What makes Electronic Beowulf so special is that it made not only high-resolution scans available, but also “forensic scans” which allowed researchers to explore areas of the manuscript previously hidden due to damage or age. Electronic Beowulf may have been the first of its kind, but it’s not the last; the Archimedes Palimpsest Project (1999-2008) was the first to use multi-spectral imaging and was followed by the Lazarus Project and Manuscripts of Lichfield Cathedral, to name a few.

Multi-spectral imaging is used to recover text or images that are damaged or illegible by scanning the document using different light wavelengths in the non-visible spectrum, including ultraviolet and infrared. This technique is especially useful for palimpsests (manuscripts in which the text has been scraped off to make the sheet re-usable) and has been integral in helping scholars discover and decipher the scrolls of St. Catherine’s Monastery at Sinai, the world’s oldest operating monastery. Multi-spectral imaging can digitally repair and re-construct texts damaged by water or light.

The Herculaneum Scrolls were studied using multi-spectral imaging as well, although they present their own problem. The papyrus scrolls were victims of the Pompeii volcanic explosion in 79 AD and as a result, are so fragile in their carbonized, rolled form that it is nearly impossible to inspect the text without damaging the object. Researchers have been experimenting with 3D x-ray imaging techniques in order to discover the contents of the scrolls.

With all of the benefits of digitization and the exciting digital projects going on, why don’t more institutions digitize their holdings? Collaboration, whether it is between staff of a single repository or multiple institutions, and collaboration between staff and users, is a necessity when dealing with digitization of special collections. Large-scale digitization projects are usually only possible with funding from external partners, such as governments or private foundations. Imaging equipment and server storage space can be very pricey, not mention the hours of (trained) staff time the digitization process consumes. Partnerships and collaboration can ease the burden – financially and time-wise – of mass digitization. (Thank you to the Council on Library and Information Resources and The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, and all the Principal Investigators of BiblioPhilly!)

The Historical Medical Library is pleased to be a part of BiblioPhilly and is looking forward to having its medieval treasures available to anyone with an internet connection. Stayed tuned to this digital space and @CPPHistMedLib – beginning Monday, January 10, the Library will be highlighting its medieval manuscripts for #MedievalMonday!