– by Wood Institute travel grantee Alexandra Prince*

If you meet a new acquaintance at a party and one of the first things they share about themselves is their membership in a newly-formed religious group, you are going to assume a few things. You might be polite enough to mask your raised eyebrows with an innocent follow-up question such as, “What is the name of the group?” Or, “What is it that you believe exactly?” But I bet that, behind your polite inquiry, you are likely wondering if they might be crazy, or if they are nuts or have a screw loose or suffer from a mental illness, or any other variety of descriptive phrases or terms we assign to people whose minds we deem not to be “normal.”

My research at the Historical Medical Library at the College of Physicians of Philadelphia in the spring of 2018 concerned the history behind this presumption that members in new religious movements are insane or somehow mentally unsound. Where did this link between religion and pathology emerge? And why are we so quick to assign mental illness to those who espouse divergent religious beliefs? To better understand the pathological frameworks we often use when discussing religion, my dissertation examines how this assumption was historically shaped. To do so, I examined the Library’s collection of archival documents relating to religion and madness during the nineteenth century.

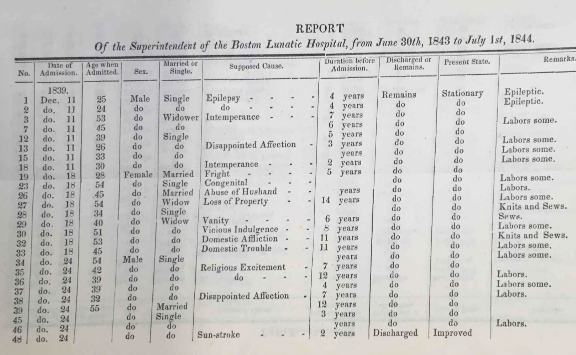

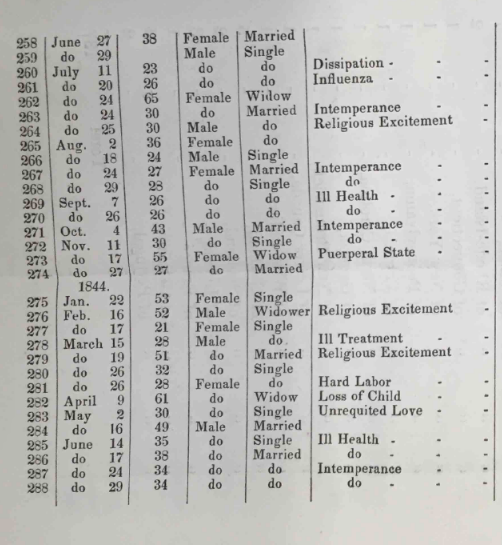

Alienists, or asylum superintendents, admitted increasing numbers of patients in connection with religion during the first half of the nineteenth century. Generally people were admitted under the nebulous disease label “Religious Excitement.” For the most part, this label was used for those men and women who engaged in popular evangelical revivalist meetings. Others were admitted under the name of the specific tradition they were aligned with, as was the case for those admitted under the label “Millerism” or “Spiritualism,” both religions which represented new beliefs and practices diverging from conservative Calvinist Protestantism. The 1844 Report of the Superintendent of the Boston Lunatic Asylum lists “Religious Excitement” and “‘Millerism’” among the causes of insanity, alongside other recognized causes such as epilepsy and intemperance. [1]

During the antebellum period, religion became one of those most commonly-cited causes of insanity in asylum superintendent reports. These reports were regularly reprinted in periodicals during a period when literacy was high and the printed word was at peak consumption by Americans. But it was no easy matter for religion to be identified as a precipitator of insanity. The idea that religion could be seen as a medical condition was troubling to those who viewed their religious faith as the antithesis of all earthly errors. British Physician John Cheyne argued passionately against the increasing association in his Essays on Partial Derangement of the Mind in Supposed Connexion with Religion published in 1843:

“We firmly believe that the Gospel, received simply, never, since it was first preached, produced a single case of insanity…We have granted that fanaticism and superstition have caused insanity, as well they may: nay, derangement of the mind may often have been caused by the terrors of the law; but by the Gospel–by a knowledge of and trust in Jesus–NEVER.” [2]

In this selection, we see how one physician reconciled the issue of religious insanity by simply and enthusiastically rejecting the “supposed connexion” between religion and madness. For Cheyne and many other physicians, it was simply a preposterous notion. Religion may be cited as the cause of insanity, but it wasn’t really religion at all. Rather it was the “abuse of religion” or fanaticism and superstition masquerading as true religion that was the culprit. The Gospel of Christianity was instead “the soberest, clearest, simplest, most cheering proposition which was ever placed before the mind of man.” [3]

What further complicates the identification of religion as a cause of madness, from a historical point of view, is that even as people were admitted to asylums in connection with their religion, the primary philosophy guiding their cure–moral management–was religiously-based. As noted in the 1840s asylum reports from the Boston Lunatic Hospital, patients regularly received religious instruction through the efforts of hired asylum chaplains. Many patients attended services in the asylum chapel, read the Bible, and were supplied with religious books, periodicals and pamphlets distributed by the American Tract Society. The tension between advocating moral management as a humane and modern treatment for the insane while at the same time increasingly attributing insanity to religion was overcome by delineating between what was generally known as “right religion,” that is, religious practice that was curative and calming in its effects, and “wrong religion” or practices that “excited” the mind. [4] [5] [6]

Amariah Brigham, asylum superintendent of the Utica State Lunatic Asylum, approached reconciling the conundrum with his work Observations on the Influence of Religion Upon the Health and Physical Welfare of Mankind. Brigham seized on the subject of popular revivalism as the utmost display of injurious and unscriptural religious activity. He argued that attendance at revivalist meetings was precipitating nervous disease in increasing numbers of people. Women, he argued, were especially vulnerable. He pointed out that the custom of holding revivalist meetings at nights, when women should be at home keeping quiet and preparing for sleep, were provoking an “excitement of the mind.” Since revivals generally seemed to attract more women than men, and especially young women, attendance at revivalist meetings were causing women to become in a sense less than women–“unfited for labor, or for the duties of a mother.” [7]

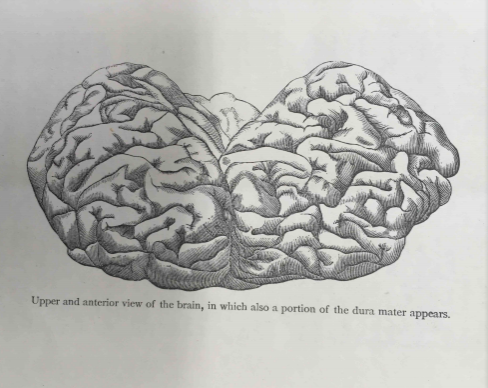

As reprehensible and unscriptural as Brigham found revivalist Christian worship to be, he nonetheless was very careful to articulate that the source of nervous disease was not religion itself but the nature and frequency of “religious night meetings,” which taxed the women’s nervous systems and ultimately weakened them to such as extent that they became vulnerable to insanity. Brigham explicated exactly how revivalism produced insanity, arguing that the mental excitement caused by such gatherings increased the blood to the brain thereby causing madness. “Insanity is not,” he wrote, “as some may suppose, merely a derangement of mind, a disease of the immortal spirit itself, but it is a disease of the brain…” [8] He explained that while it was common to speak of the mind as being deranged, in fact the mind’s derangement was only a symptom of a physical disease of the brain. Just in case any one doubted the sincerity of his faith, Brigham dedicated the book in the hope “that it will have some influence in restoring the worship of Christians to that calm, simple and pure manner, recommended by our Saviour.” [9] Despite his efforts, Brigham’s attempts to attribute insanity to the “exciting” aspects of some religious practices while still remaining deferential to Christianity failed. His work was labeled blasphemous and produced a torrent of rebuke.

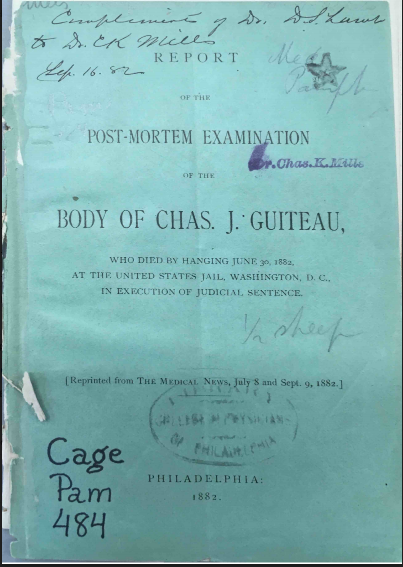

High-profile legal cases involving alleged religious madness continued to make headlines during the turn of the century thus further underscoring the connection between religion and insanity in the public imagination. In a final example from the library’s archives, we have the case of Charles J. Guiteau, the man who assassinated President Garfield in 1881. During his trial, physicians were called in as expert witnesses to adjudge Guiteau’s insanity and determine the legitimacy of his insanity plea defense. Coverage of the trial became a media spectacle widely consumed by scandal-loving readers. Americans were introduced to Guiteau’s strained participation in the Oneida Community, a Christian communal society, and later his alleged call from God to murder the president. According to neurologist George M. Beard, Guiteau’s type of insanity was clear. Beard wrote in his article “The Case of Guiteau–A Psychological Study” that Guiteau suffered from religious monomania, or a hyper-attention to the subject of religion. “Although only a part of his delusions were of a distinctively religious character,” explained Beard, “they all, when traced to their ultimate radicals, had a religious origin, and were complicated with distinctive religious delusions from which he was never free.” [10]

The brain of Guiteau is now part of the collection of the Mütter Museum, preserved after a post-mortem examination performed in part by a Fellow of the College. This examination was motivated by questions concerning the physical indicators of insanity in the brain. Citing lesions on the corpus striatum as well as the frontal region of the cerebral cortex, the committee reviewing the findings reported that they had “no hesitation whatever in affirming the existence of unquestionable evidence of decided chronic disease.” [11] The insanity trial of Guiteau would continue to be evoked in newspapers and medical journals for years.

The idea of the religiously insane as murderer, a trope well-established by Guiteau’s time, strengthened with future cases of supposed religious insanity among members of new religious groups. Today, few hesitate to use the language of pathology when discussing certain religious traditions (think Jim Jones and the People’s Temple movement). It is a commonplace presumption that frames our consideration of fringe religious identities we find subversive or frightening. Yet our understanding of the line between faith and madness, between spiritual inspiration and mental delusions, remains far from clear.

Endnotes

[1] Report of the Superintendent of the Boston Lunatic Asylum and Physician of the Public Institutions at South Boston. Boston: John H. Eastburn, 1844, 5-6.

[2] Cheyne, John. Essays on Partial Derangement of the Mind in Supposed Connexion with

Religion. Dublin: Curry, 1843, 144.

[3] Ibid., 143.

[4] Reports of the Superintendent of the Boston Lunatic Asylum and Physician of the Public

Institutions at South Boston. Boston: John H. Eastburn, 1840/1841/1843/1844/1845.

[5] Report of the Board of Visitors and of the Superintendent of the Boston Lunatic Asylum. Boston: John H. Eastburn, 1848.

[6] Report of the Board of Visitors and of the Superintendent of the Boston Lunatic Hospital,

Containing a Statement of the Condition of that Institution, and Transmitting the Annual Report of the Superintendent for 1850. John H. Boston: John H. Eastburn, 1850/1851.

[7] Brigham, Amariah. Observations on the Influence of Religion upon the Health and Physical Welfare of Mankind. Boston: Marsh, Capen & Lyon, 1835, 146.

[8] Ibid., 274.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Beard, George Miller. “The Case of Guiteau–A Psychological Study.” Reprinted from The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, Vol. 9, No. 1, January, 1882.”

[11] Lamb, Daniel Smith. Report of the Post-mortem Examination of the Body of Chas. J. Guiteau: Who Died by Hanging June 30, 1882, at the United States Jail, Washington, D.C., in

Execution of Judicial Sentence. Philadelphia: 1882. Reprinted from The Medical News, July 8 and Sept. 9, 1882.

*Alexandra Prince is a PhD Candidate in the History Department of the University at Buffalo. She received an F.C. Wood Institute Travel Grant from the College of Physicians of Philadelphia in May 2018. You can follow her blog at sabbathways.wordpress.com.