– by Wood Institute travel grantee Dr. Edward Allen Driggers*

Historians take for granted the ways in which the profession produces knowledge. Usually historians construct a question from the historiography or primary sources that they encounter. I think occasionally, though, Clio speaks and we are inspired. I recently completed one of the most dynamic years of my life: my daughter was born into the world, I completed my Ph.D. in the history of science, and I completed my first year on faculty in the history department at Tennessee Technological University. My recent research trip to the Historical Medical Library at the College of Physicians of Philadelphia did the same thing for me that it did in 2014 under my first Wood Institute travel grant: it allowed me to be quiet and let the muse speak. It was inspiring.

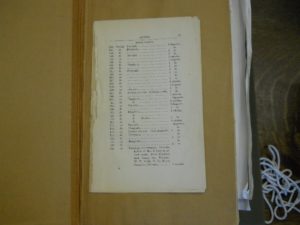

My research is about urinary stones—earning me a reputation for less-than-appealing small talk. Urinary stones fall into a vexing medical and surgical problem at the turn of the nineteenth century: how to effectively treat sufferers of morbid concretions (stones that appeared in the urinary organs, uterus, brain, lungs, and in other cavities of the body). The best way to learn about urinary stones during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century was to collect stones for further research. While I was at the College, I was able to examine the catalogue of the Mütter Museum, where the Museum lists its large collection of urinary stones from humans.

I write about communities of physicians and surgeons who pursued chemical knowledge to improve the treatment of urinary stones. I examined three communities located in Philadelphia, Charleston, and London. Since the study takes place at the turn of the nineteenth century, I also examine how these medico-chemists and surgeons attempted to use the new chemistry of Antoine Lavoisier to study urinary stones. Surgeons and physicians perceived urinary stones to be the result of an imbalance of the body’s fluids. Many tried to find chemical ways to break the stones down into their base chemicals. Some of the medico-chemists and surgeons referred to these interventions as resembling humoral practice.

An example of the close chemical analysis and experiments on urinary stones comes from the dissertation of William Steven Jacobs of Barbant (France) published in 1801. The illustrations were hand done, and have an artistic quality to them. Many medical students at that time were learning to quantify and categorize stones in the hopes of finding an insight into how stones formed, or presented in patients, in the hopes of contributing to the growing body of chemical knowledge.

Surgeons were viewed by both physicians and chemists as having the only guaranteed way to remove the stone from the body – the lithotomy. A lithotomy was a surgical procedure that removed the stone from the bladder. While I was at the Historical Medical Library, I was able to view Robert Allen’s A Treatise on the Operation of the Lithotomy, published in 1808. This treatise is a work of art, as it contains many detailed plates that teach the intricacies and difficulties of the operation. A patient suffering with stones would not have taken this dangerous and painful operation lightly. This is one reason why both medico-chemists and surgeons sought a chemical alternative to surgical removal of stones; seeing images of this operation further reinforces those ideas.

It is one thing to write about the history of the chemistry of urinary stones; it is another thing to take a lunch break from doing so and wander the Mütter Museum, where urinary stones of all shapes, sizes, and chemical compositions are on display.

Though many dissertations have been digitized through Hathi Trust, or other similar databases, it is more meaningful to read the original chemical compendiums that the individuals at the heart of your dissertation (now book project) read and examined while they were students in the Medical College of the University of Pennsylvania. One such person, Edward Darrell Smith, a South Carolina born physician who was trained in medicine and chemistry at the University of Pennsylvania, sent a copy of his dissertation to be housed at the College of Physicians of Philadelphia.

The Historical Medical Library was energizing, as was Philadelphia itself. I accidently scheduled my trip right before and during the opening days of the Democratic National Convention. After a brisk day in the Library reading and photographing sources concerning urinary stones and surgery, I spent my afternoons listening to the news. It made for congested travel, as many of the DNC delegates rode the spur to the Wells Fargo Arena.

The research collection inspired me to continue to work on transforming my dissertation into a book. I found an incredible source that brought together the disparate parts of my work. It helped to answer how surgeons were absorbing chemical knowledge beyond simply collecting stones in order to prepare their students for what they would remove during lithotomy. One surgeon, John Syng Dorsey, wrote a dissertation in 1806 arguing for the usefulness of the gastric liquor in treating urinary stones. A biography can be found about Dorsey in the journal Surgery (1988: Volume 103, issue 1, pgs. 45-55). He opened his dissertation by writing that the search for a chemical remedy for stones would be something of great value to all mankind, and that surgery for the stone seemed to represent the failing of medicine as a whole. Dorsey believed that a proper fluid, like gastric fluid that existed in the intestine, could be used to shrink stones inside the body. Dorsey pointed out that concretions were known to occur in the intestines and that this fluid destroyed them. He wrote that perhaps a method could be developed to inject the acid into the body and prevent the need for the operation. Dorsey performed several experiments with subjects suffering from the stone:

The most simple method of ascertaining the effects of the Gastric liquor of the human stomach appeared to consist of swallowing a portion of stone. I enclosed a fragment of calculus in a silver sphere, perforated with a number of foramina; this sphere was swallowed by a healthy young man; it was discharged in sixty-five hours, * and weight but five grains, this remainder was very much softened. (22)

My time at the College has inspired new linkages between surgeons and physicians interested in using chemistry to treat the stone in the bladder. Finding sources like Dorsey’s dissertation united two disparate chapters and groups that seemed to not have much to do with each other, or were unaware that they were working on the same questions. I would have never seen a source like Dorsey otherwise, and having the time to read the documents closely at the Library allowed me to make connections between medicine, surgery, and chemistry at the turn of the eighteenth century.

*Dr. Edward Allen Driggers is an Associate Professor of History at Tennessee Technological University. He received an F.C. Wood Institute Travel Grant from the College of Physicians of Philadelphia in July 2016.