– by Wood Institute Travel Grantee Elena Jarmoskaite*

It was in the scorching heat of summer 2018 that I arrived in Philadelphia, having travelled some three and a half thousand miles separating the Historical Medical Library and my home in London. I came here for the sole purpose of learning more about the phenomenon most of us would happily never hear about again: the anti-vaccinationists, or, colloquially, the anti-vaxxers.

Not that long ago I would have seen vaccination opponents as a merely baffling movement, perhaps not all that distinctly removed from other fringe groups like the infamous flat-earthers or tin foil-hat-wearers; at the point of my visit, however, they had become central to my Master thesis. A lot has been said about the anti-vaccinationists, and it is an increasingly hot topic at the moment, with unfortunate and unignorable outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases happening all over the globe. Vaccination opposition, however, is a difficult subject, both because of its multi-layered nature, and because of the immense amount of emotion surrounding it.

It is this emotional aspect of the subject that I chose to focus on. My background is in design, and as a budding design historian at the Royal College of Art and Victoria and Albert Museum in London, I looked at anti-vaccinationists through the lens of their visual and verbal rhetoric. We know a lot about what anti-vaccinationists believe, but we have not paid much attention to why it is they choose to believe in theories so widely discredited. What speaks to them? How are they spoken to? How are the anti-vaccinationist ideas distributed, and how have they been able to stand the test of time?

Yes, the test of time. One of the first things to note is that while anti-vaccinationism is sometimes presented as yet another symptom of flawed twenty-first century society, it has in fact been around as long as vaccines themselves. The College of Physicians of Philadelphia’s own History of Vaccines website (https://www.historyofvaccines.org/) is an excellent source to correct this presumption, and one that eventually lead me here.

However, while vaccines (and the preceding forms of immunisation) quite naturally attracted skepticism when the procedure was still new, this skepticism became the basis of a growing number of anti-vaccination activist groups from the nineteenth century onwards. It was the Historical Medical Library’s holdings of one of these groups – the Anti-Vaccinationist Society of America – that I travelled here to see.

(I would learn, too, that the Society is believed to have been founded after an earlier visitor from Britain, William Tebb, made this trip across the ocean to bring some passionate ideas about vaccination. The infamous author of the discredited autism study, Andrew Wakefield, has also come stateside from Britain to preach his ideas. One can only hope that another traveller on this route will one day help make a dent in their legacy. It definitely feels worth a try.)

While the Historical Medical Library possesses a sizeable collection of documentation pertaining to the Anti-Vaccination Society of America (as well as some other associations in the country and abroad), the focus of my research was two scrapbooks which contained a varied collection of anti-vaxx ephemera produced by the Society. My goal was to compare and contrast this material with the vast body of twenty-first century communication material I collected online; by employing a carefully considered theoretical framework, I wanted to see how much the strategies behind the attempts to convince people to reject vaccination have changed over the years. What images did the anti-vaccinationist societies use to get their point across? What distribution modes did they use to reach their audiences? Who did they target, and how did they change their tone depending on who they were talking to? What was their language like, both visually and verbally? How were the images and the text linked? Did they try to target people’s love for their children, their stance on their civil liberties, their feelings about the Government’s interference with their private lives? Was the underlying suspicion about conspiracies (fully adjustable to their political leanings) as lively then as it is now?

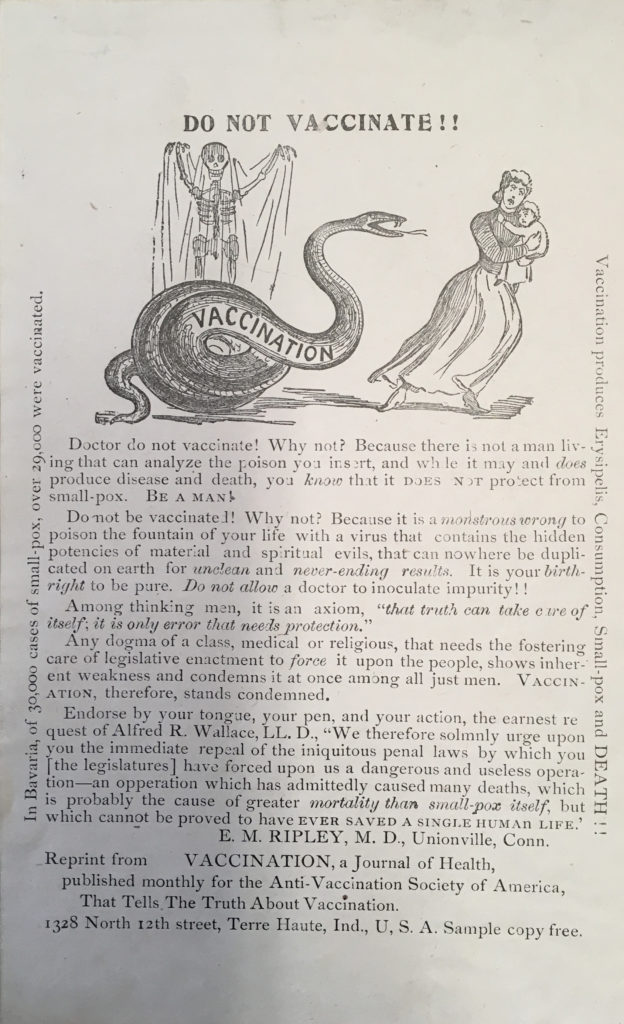

As a thought exercise, I invite you, too, to spend a minute or two considering these questions while looking at two of the pieces I ended up scrutinising in my dissertation – a double-sided photographic leaflet featuring Alma Olivia Piehn, and a single-sided illustrated leaflet portraying an evil embodiment of vaccination. Both the photograph and the drawing appear repeatedly in many other examples of anti-vaccinationist ephemera, sometimes alongside completely different text.

I want to believe I have a better inkling about some of the above questions now, having spent days with the material in the library, and weeks with the hundreds of digital copies I made when I was back in England. As time passes, however, I understand more and more that completely conclusive answers are simply not possible. Communication encouraging us to believe things (or rid us of our beliefs) is at its most powerful when it taps into our biases, and our own biases will inevitably prevent us from assessing it in a fully neutral way even in a rigorously academic setting. My main takeaway, though, is that merely asking these questions is absolutely critical on its own. And it should not be contained in the library rooms where we pore through the fascinating historical material to understand people before us. This criticality is crucial in our everyday interaction with ourselves and those around us, now.

I will never forget the feeling of leafing through the frail, discoloured leaflets, newspaper clippings and photographs collected in the scrapbooks, and wondering how the members of the Anti-Vaccinationist Society of America would feel knowing that these cheaply printed ephemeral pieces survived to see the twenty-first century. The Society no longer exists, but it has been succeeded by countless other organisations, still in full operation now. Their crusade has not achieved the victory they envisioned.

But they have not lost yet, either.

Select Bibliography

[Scrapbook of Anti-Vaccination Clippings]

Minutes, Correspondence, etc., 1885-1898 (Anti-Vaccination Society of America)

The Anti-Vaccination News and Sanatorian

Both Sides of the Vaccination Question

*Elena Jarmoskaite recently completed a MA in the History of Design program at the Victoria &Albert Museum and the Royal College of Art in London. he received an F.C. Wood Institute Travel Grant from the College of Physicians of Philadelphia in August 2018.